Genre-based approach for teaching academic writing for undergraduate engineering students

Nguyen Thi Tu Trinh1*

Department of Advanced Science and Technology, University of Science and Technology, The University of Da Nang, Vietnam

ABSTRACT

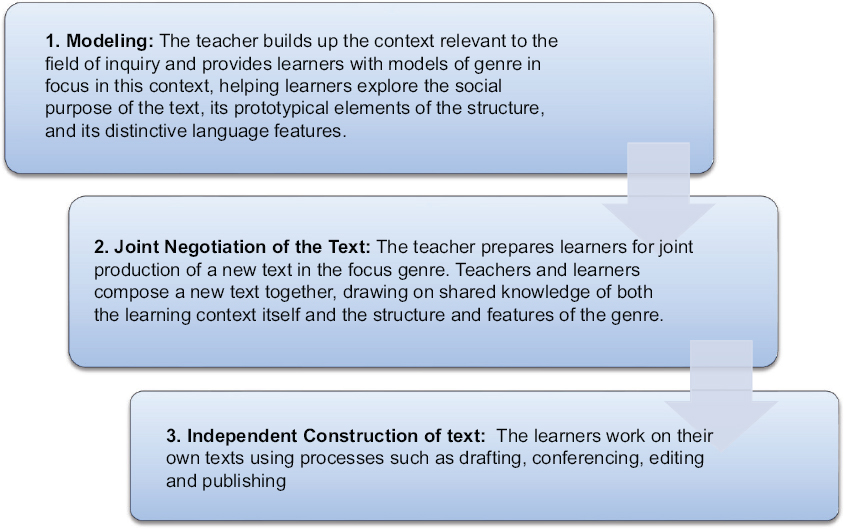

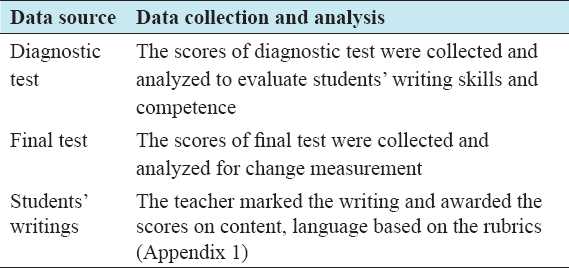

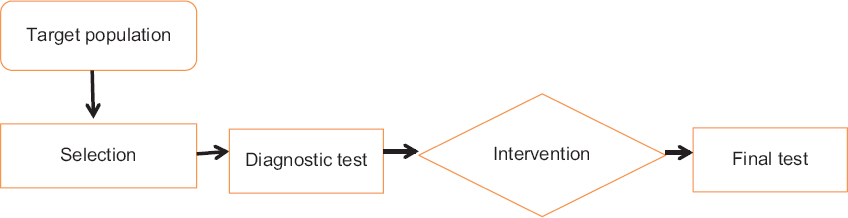

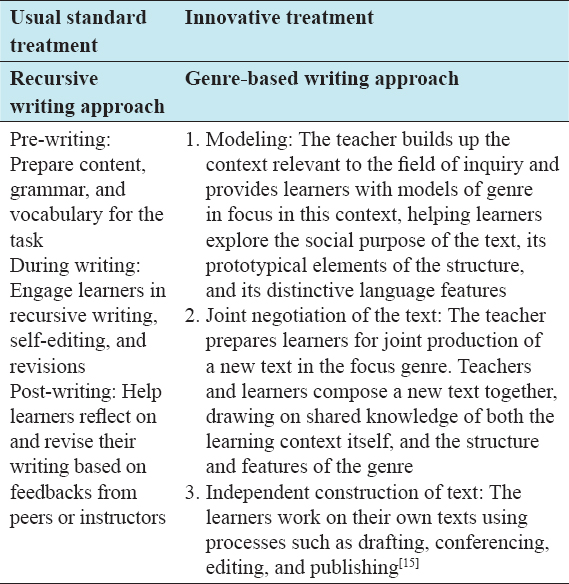

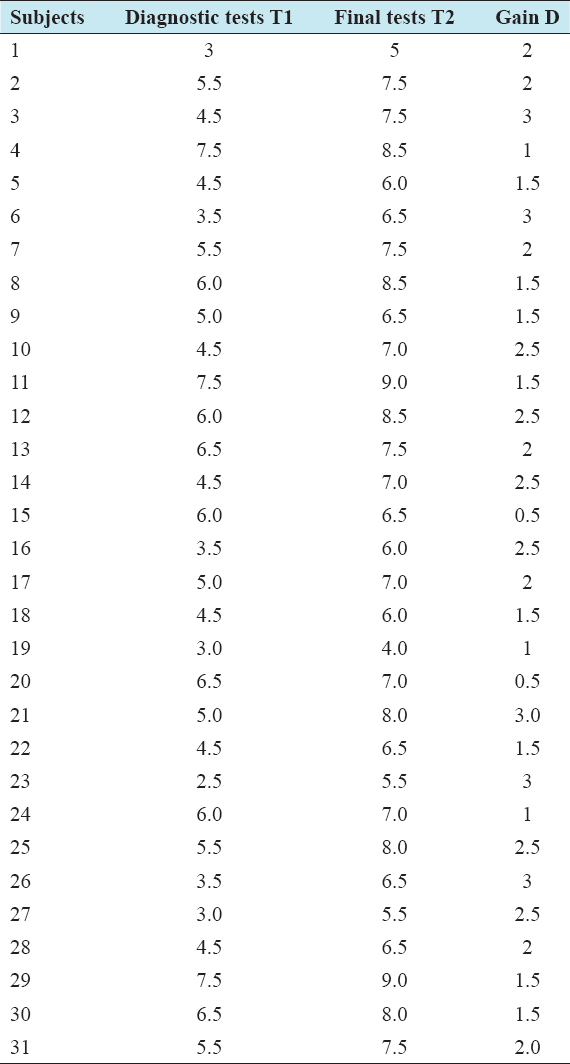

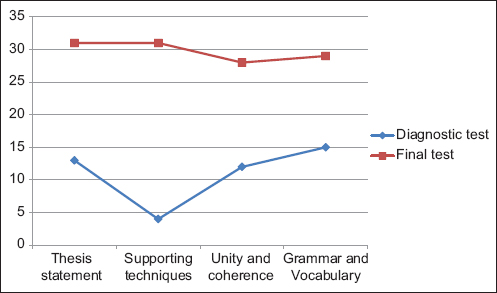

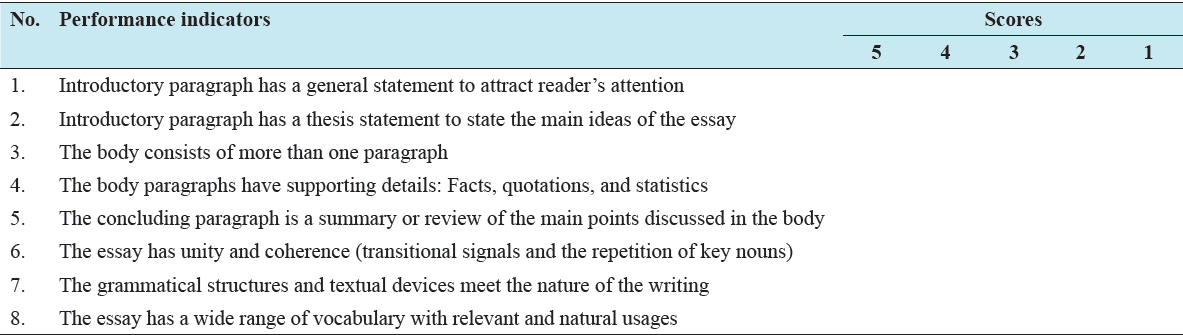

It is commonly agreed that academic writing for undergraduate non-native English students is a daunting task because of the low entry level of their English proficiency as well as lack of academic writing skills. A lot of attention has been paid to the writing teaching approaches to help the students learn about writing process, writing content, and genre-based perspectives have emerged as a new approach to teaching and learning academic writing. This study is carried out to (1) examine a practical application of Macken’s framework of teaching writing within genre-based perspectives in the University of Science and Technology – the University of Da Nang and (2) investigate the effectiveness of genre-based perspectives in teaching academic writing for undergraduate students by analyzing the assessment instrument rubric of the diagnostic and final test. The subjects consisted of 31 freshman undergraduate engineering students at the University of Da Nang during the first semester of 2020 academic year. The instruments used in this experiment include the students’ diagnostic tests, lesson plans, and their final tests. The study reveals that with the implementation of innovative treatment – genre-based writing approach, a majority of students achieved their impressively high gain score in their final writing tests as well as made good progress in their writing performance and skills.

Keywords: Academic writing, genre-based approach, undergraduate students